Why do we feed wild birds?

Bird feeding - it is massive!

Let’s get one thing straight, the importance of feeding wild birds should not be underestimated - it is quite simply massive. On many levels. As a business, estimates vary between £200-300 million pounds per annum are generated just in the UK. The fields, that grow the seed mixes, which fill our feeders, are industrial in size and so are the warehouses that store it. As a pastime, the number of people who feed wild birds in their gardens, or on their balconies, varies between 40-50% of all households and this does not even take into account the more informal feeding of our wildfowl in the local park. More importantly, this practice has an, as yet, unfulfilled capacity to engage, re-engage and energise our relationship with the natural world. This at a time when there is an increasing recognition in both scientific and social channels of the importance of nature for our physical and mental well-being, whilst the degradation of the environment and loss of species is becoming a hot topic within mainstream media.

But why do we do it?

A few years ago, I started to wrestle with this question and to navigate the arduous corridors of academia to give a scientific dimension to any answers. Was it just about a self-centred joy and pleasure we get from this activity or was it about a more altruistic motive, the birds survival? To go forwards, it is always a good idea to check out what has been before and there had been surprisingly little research done on the human part of this common day activity. Lots and lots of scientific papers on how feeding may, or may not, affect birds but little about us.

I’m guessing that we have probably fed birds from when we were cave dwellers, but it is our relationship with bread that gives credence to a long history of feeding wild birds. We`ve been making bread across societies for over 10,000 years, indicating a change from nomadic to sedentary agricultural lifestyles, whilst the breaking of bread cannot be underestimated. It is deeply embedded in our psyches. Across societies and religions, it symbolised, and symbolises, sharing and caring and goes hand in hand with a ritualistic aspect. And where there is grain there are birds. Spread the seed in the chicken coop and the sparrows will congregate.

This religious theme continues through bird feeding history with various hermitic saints practising goodwill to birds and other animals, but it's not until the Renaissance, and into the 18th century, that the factual mentions start to mount up - often in the context of a large house with grounds, an upper class household, crumbs and plenty of largesse.

When we get to the 1890’s, the practice really accelerates. During this decade, Britain was in the throes of chronically hard winters, and in urban centres it was common to see birds in distress and dying through cold and lack of food. In London, Gulls, previously rarely seen inland, were becoming part of the common tapestry of the Thames and where two decades previously it was common sport to shoot them, now workers were sharing their lunches with them.

This informal feeding rapidly became more formalised with the introduction of bird feeders and tables. Where once it was winter feeding, it is now all year round, where once it was scraps left in the garden, on the windowsill or thrown from a London bridge, it is now so sophisticated that seed mixes are being sold on the strength of the types of birds they will attract and by inference the species they may deter, playing on the deeply engrained ambivalence we still have for birds…we still eat them, shoot them for sport, we have favourites, whilst enjoying their antics in our gardens and chasing across the country when a rare species flies in.

This history lesson suggests that our motivations are from a mix of drivers that are anthropocentric, e.g. pleasure, and eco centric or avian centric, such as bird survival…but is there more to it than this?

Let’s go to the science

The research itself was based in London and the South East where 30 individuals, who fed birds regularly, were interviewed in depth about their habits and motivations. These interviews often lasted well over an hour and formed the basis of a distillation into an online questionnaire in which over 500 people feeding birds took part, Approximately 50% were members of environmental organisations, such as the RSPB, BTO and Wildlife Trusts. A big thank you goes to London Wildlife Trust and BTO for helping supply many of these respondents. From this qualitative element, nine major themes were elicited, which fed into the quantitative part of the research, which produced the numbers as expressed graphically within the paper which you can find by clicking here.

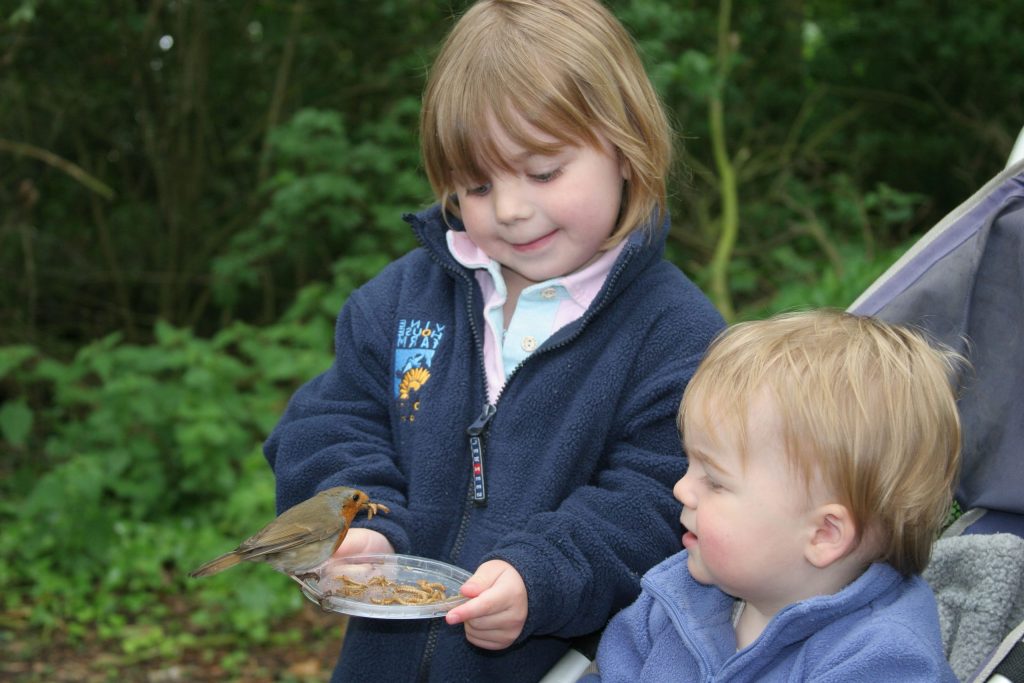

Pleasure and bird survival were confirmed as the two most important motivators to feed wild birds, alongside nurture, being close to nature, children’s education, not wasting food, personal atonement, companionship and making amends. Not all respondents would have all these nine motivations operating, but the research showed that such a simple practice has potentially complex themes operating. These drivers have been formed through equally complex cultural roots. Our historical relationships with birds through domestication, pet ownership and garden stewardship, our innate need to be close to nature, themes of austerity reinforced by two world wars and environmental guilt, as it is slowly dawning on us how we have negatively impacted on nature. Furthermore, for respondents with children, there was a strong drive to pass on this interest and recognition that a trigger to feed is often instilled at a young age.

What was a striking element of the research findings was the real depth of feeling and importance that respondents placed on the practice. ‘They are the world to me’, ‘I don’t know what I would do without them’, ‘I get lost in their world’, were just some of the quotes that displayed a profound connection with the birds that visited the respondents gardens.

As with all research, more questions than answers have been posed, particularly the need to unpick what we mean by pleasure. From the interviews, this pleasure seems to encompass the softer side of the human psyche; spirituality, wonder and awe, but also harder edged themes of control, paternalism and domination. The research also suggests the untapped potential for engagement, and barriers to engagement, as the majority of respondents declared themselves as white and over 35 years old. It should be classless, ageless, raceless and creedless.

In an increasingly urbanised society, where urban green spaces are becoming more important, yet more threatened, there is an increasing concern that millennials will suffer from an extinction of environmental experience. Bird feeding offers a direct interaction with wildlife at home, and in communal spaces, with little financial investment and very little effort. The trick will be to communicate the over-riding pleasure that can be experienced through feeding birds and the potential care for our environment that this can generate for all of our health and well-being; that’s massive.

© Dave Clark

Dave Clark has an MSc in Ornithology from the University of Birmingham, is an ornithologist and environmental campaigner with a particular interest in the interactions between birds and humans. dave@mailbox.co.uk

Let’s get one thing straight, the importance of feeding wild birds should not be underestimated - it is quite simply massive. On many levels. As a business, estimates vary between £200-300 million pounds per annum are generated just in the UK. The fields, that grow the seed mixes, which fill our feeders, are industrial in size and so are the warehouses that store it. As a pastime, the number of people who feed wild birds in their gardens, or on their balconies, varies between 40-50% of all households and this does not even take into account the more informal feeding of our wildfowl in the local park. More importantly, this practice has an, as yet, unfulfilled capacity to engage, re-engage and energise our relationship with the natural world. This at a time when there is an increasing recognition in both scientific and social channels of the importance of nature for our physical and mental well-being, whilst the degradation of the environment and loss of species is becoming a hot topic within mainstream media.

But why do we do it?

A few years ago, I started to wrestle with this question and to navigate the arduous corridors of academia to give a scientific dimension to any answers. Was it just about a self-centred joy and pleasure we get from this activity or was it about a more altruistic motive, the birds survival? To go forwards, it is always a good idea to check out what has been before and there had been surprisingly little research done on the human part of this common day activity. Lots and lots of scientific papers on how feeding may, or may not, affect birds but little about us.

I’m guessing that we have probably fed birds from when we were cave dwellers, but it is our relationship with bread that gives credence to a long history of feeding wild birds. We`ve been making bread across societies for over 10,000 years, indicating a change from nomadic to sedentary agricultural lifestyles, whilst the breaking of bread cannot be underestimated. It is deeply embedded in our psyches. Across societies and religions, it symbolised, and symbolises, sharing and caring and goes hand in hand with a ritualistic aspect. And where there is grain there are birds. Spread the seed in the chicken coop and the sparrows will congregate.

This religious theme continues through bird feeding history with various hermitic saints practising goodwill to birds and other animals, but it's not until the Renaissance, and into the 18th century, that the factual mentions start to mount up - often in the context of a large house with grounds, an upper class household, crumbs and plenty of largesse.

When we get to the 1890’s, the practice really accelerates. During this decade, Britain was in the throes of chronically hard winters, and in urban centres it was common to see birds in distress and dying through cold and lack of food. In London, Gulls, previously rarely seen inland, were becoming part of the common tapestry of the Thames and where two decades previously it was common sport to shoot them, now workers were sharing their lunches with them.

This informal feeding rapidly became more formalised with the introduction of bird feeders and tables. Where once it was winter feeding, it is now all year round, where once it was scraps left in the garden, on the windowsill or thrown from a London bridge, it is now so sophisticated that seed mixes are being sold on the strength of the types of birds they will attract and by inference the species they may deter, playing on the deeply engrained ambivalence we still have for birds…we still eat them, shoot them for sport, we have favourites, whilst enjoying their antics in our gardens and chasing across the country when a rare species flies in.

This history lesson suggests that our motivations are from a mix of drivers that are anthropocentric, e.g. pleasure, and eco centric or avian centric, such as bird survival…but is there more to it than this?

Let’s go to the science

The research itself was based in London and the South East where 30 individuals, who fed birds regularly, were interviewed in depth about their habits and motivations. These interviews often lasted well over an hour and formed the basis of a distillation into an online questionnaire in which over 500 people feeding birds took part, Approximately 50% were members of environmental organisations, such as the RSPB, BTO and Wildlife Trusts. A big thank you goes to London Wildlife Trust and BTO for helping supply many of these respondents. From this qualitative element, nine major themes were elicited, which fed into the quantitative part of the research, which produced the numbers as expressed graphically within the paper which you can find by clicking here.

Pleasure and bird survival were confirmed as the two most important motivators to feed wild birds, alongside nurture, being close to nature, children’s education, not wasting food, personal atonement, companionship and making amends. Not all respondents would have all these nine motivations operating, but the research showed that such a simple practice has potentially complex themes operating. These drivers have been formed through equally complex cultural roots. Our historical relationships with birds through domestication, pet ownership and garden stewardship, our innate need to be close to nature, themes of austerity reinforced by two world wars and environmental guilt, as it is slowly dawning on us how we have negatively impacted on nature. Furthermore, for respondents with children, there was a strong drive to pass on this interest and recognition that a trigger to feed is often instilled at a young age.

What was a striking element of the research findings was the real depth of feeling and importance that respondents placed on the practice. ‘They are the world to me’, ‘I don’t know what I would do without them’, ‘I get lost in their world’, were just some of the quotes that displayed a profound connection with the birds that visited the respondents gardens.

As with all research, more questions than answers have been posed, particularly the need to unpick what we mean by pleasure. From the interviews, this pleasure seems to encompass the softer side of the human psyche; spirituality, wonder and awe, but also harder edged themes of control, paternalism and domination. The research also suggests the untapped potential for engagement, and barriers to engagement, as the majority of respondents declared themselves as white and over 35 years old. It should be classless, ageless, raceless and creedless.

In an increasingly urbanised society, where urban green spaces are becoming more important, yet more threatened, there is an increasing concern that millennials will suffer from an extinction of environmental experience. Bird feeding offers a direct interaction with wildlife at home, and in communal spaces, with little financial investment and very little effort. The trick will be to communicate the over-riding pleasure that can be experienced through feeding birds and the potential care for our environment that this can generate for all of our health and well-being; that’s massive.

© Dave Clark

Dave Clark has an MSc in Ornithology from the University of Birmingham, is an ornithologist and environmental campaigner with a particular interest in the interactions between birds and humans. dave@mailbox.co.uk